On March 15, when Judge James E. Boasberg verbally ordered the U.S. government under Donald Trump to halt the deportations of Venezuelan migrants from Harlingen Airport in Texas, Franyeli Carolina Zambrano Manrique was already on the plane, dressed in blue pants, a gray pullover matching her shoes, and handcuffed at both her hands and feet, which made it uncomfortable every time she tried to take a bite of her sandwich or sip of water.

By that time — 6:48 p.m. — the first flight from Global X airline was already flying over Mexican skies, and a second was moving over the Gulf of Mexico (Gulf of America, according to Trump). Ignoring the warning from the judge of the U.S. District Court of Washington, a third plane, the one carrying Franyeli, was preparing to take off. Franyeli thought it was flying to Simón Bolívar Airport in the Caracas metropolitan area. But that never happened.

“I felt both joy and sadness to be returning to Venezuela,” says Franyeli, 30.

A total of 18 women were set to be deported, but only eight boarded the plane at the Texas airport. The officers were in a hurry, they didn’t want to waste time, nor did they want anything to prevent them from carrying out the expulsion. Franyeli had told her family that she would arrive in Caracas, and in Maracaibo, her father and five children were waiting for her. The other women made similar arrangements. Scarleth Rodríguez, for example, asked her mother in Antímano to have a stewed chicken ready for her.

However, the eight Venezuelan women, according to them and their families, were “kidnapped” and “deceived” by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents. It wasn’t until hours later that they discovered they hadn’t been taken to Caracas, but had first landed in Guatemala and then in El Salvador.

The previous days had been the longest of Franyeli’s life. On Saturday, February 8, she was driving with her husband, Rolando Barreto Villegas, 34, to St. George, Utah, where they planned to spend the weekend in a hotel room. Around 4 p.m., two immigration officers stopped the car. Upon confirming the two were Venezuelan, they informed them that they had arrest warrants, even though Franyeli and her husband were in the country as beneficiaries of Temporary Protected Status (TPS). Once at the ICE office, the officers asked what they did for a living. She worked as a manicurist; he worked in construction. They had been married for 10 years.

They also asked if Rolando was prostituting her or if they belonged to any criminal gang. They said no. The couple were asked if they had tattoos. They did. Some matched the list of drawings the officers showed them, which included stars, crowns, a lion, a rose, and phrases like “Real hasta la Muerte” and “Daughters of God.”

Franyeli and Rolando refused to sign the document admitting they were members of the Tren de Aragua criminal gang, but it didn’t matter. That was, in fact, the moment their long journey back. They couple were handcuffed and transferred to the Henderson detention center in Nevada, where officers “kicked the food with their feet, and if it spilled, they would pick it up from the floor.” After a month in confinement, guards arrived at the two-by-four-meter cell Franyeli shared with another Venezuelan inmate. They woke her up. Franyeli found it strange. It was 3 a.m. on a Friday. “I always saw deportations happening on Tuesdays, so I was really surprised,” she says.

Franyeli asked where they were taking her, but the officer couldn’t understand her Spanish, and she didn’t understand his English. Among many words, she heard him say “ICE,” but she couldn’t figure out what they were doing with her. After a few hours, she learned she was going to be deported to Venezuela. “Obviously, I was happy,” she confesses.

Handcuffed, they transferred her to another detention center where she saw her husband along with a group of Venezuelan men. She thought they were going to send them together to their country. On Saturday, March 9, they were put on a plane that landed in Washington, where they picked up 17 men and two other women. They took off towards Texas.

Six days later, they were loaded onto buses packed with other migrants and taken from the detention center to the airport. Scarleth, 21, was euphoric. She had been in detention for nine months, ever since turning herself in to border authorities in August 2024. She had never been allowed to leave prison, and now, even though she was being deported, she would be free.

“She was happy because she was coming back to Venezuela,” says her mother, Yelitza Rodríguez, a street vendor in Antímano, who had prepared the stewed chicken her daughter requested before leaving the U.S. “I felt like she was going to show up and surprise me, cover my eyes from behind.”

“ICE officers wouldn’t let us open the window blinds on the plane”

Almost an hour after the first order to halt deportations, Judge Boasberg issued a second directive — this time in writing — ordering the Trump administration to return the three planes that had departed from Harlingen back to U.S. soil. By then, the first flight had already landed in Guatemala, the second was flying over Mexico, and the third was still on the ground. Just a day earlier, Trump had signed an executive order invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 — a wartime law now being used to justify the expulsion of people deemed part of an invading force.

The Global X flight carrying Franyeli eventually took off, despite the judge’s ruling. Her husband was on another plane. Franyeli doesn’t remember exactly how long the flight lasted, but it felt endless. If she needed to use the restroom, an ICE officer would escort her. The eight women found it strange that the plane’s windows were kept covered the entire time. “The officers never let us open the window blinds on the plane,” says Franyeli.

When the plane landed for the first time, they were told they were in Guatemala, but that they would continue on to Caracas. When it landed a second time, the women realized on their own that this was not their country. “Girl, this isn’t Venezuela — there’s way too much riot gear,” said one of them after managing to lift a blind. When Franyeli peeked out, she saw it was indeed somewhere else. “We started crying, the men started yelling, saying we weren’t getting off,” she recalls.

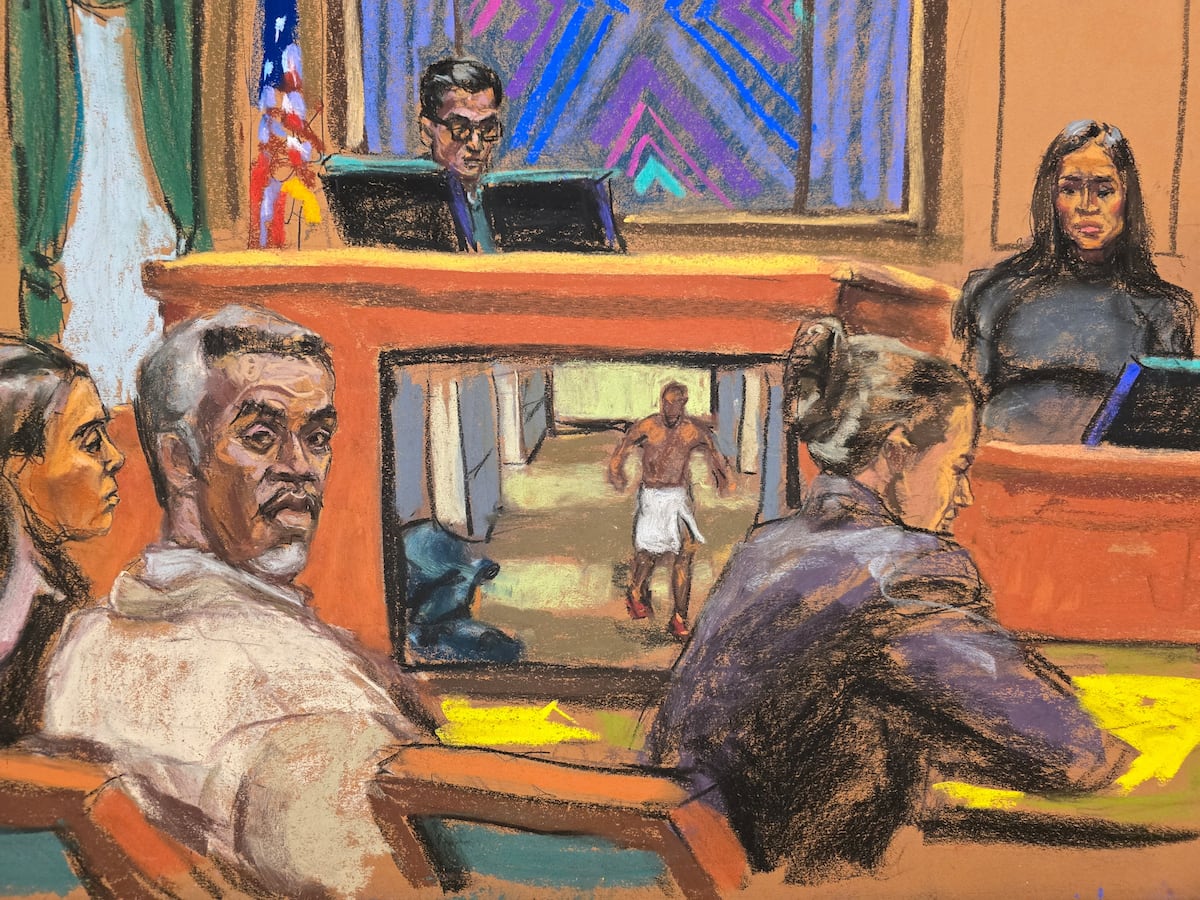

Amid the commotion, their refusal to sign the documents they were given, and the shouting, one officer “became violent.” Franyeli recalls how the ICE agent, with identification number HOU-02, slapped a woman and dragged another another down the aisle of the plane. All of them were frightened to see, through the window, the way men from another flight were being removed. “They grabbed them, threw them down the stairs, and when they hit the ground, they picked them up and dragged them out,” Franyeli says.

Those men were the 238 detainees the world would later see in images released by Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele, being practically dragged down the steps of a plane, shackled and dressed in white, to the Terrorism Confinement Center (CECOT). This is the mega-prison, with capacity for up to 40,000 inmates, that the Salvadoran government made available to the U.S. for housing deported Venezuelan migrants. It’s the same facility Bukele proudly showcases, which conceals a terrifying prison system that holds around 120,000 prisoners — the highest incarceration rate in the world.

Since then, human rights organizations and judges have condemned the transfer of Venezuelan detainees to El Salvador, arguing that it violates due process. A Human Rights Watch (HRW) study found that, out of 40 Venezuelans deported to the Central American country, none had criminal records. HRW has also classified these deportations as “forced disappearances.”

The detainees have not only been cut off from family and legal counsel, but also denied the ability to attend court hearings in the U.S. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has not released an official list of the names or exact number of people sent to El Salvador — a group that was later joined by other Venezuelans. On March 31, the State Department announced that 17 alleged gang members had been deported there, and on April 13, El Salvador’s security minister confirmed they had received another 10 people from Guantánamo.

Neither the list made public by CBS News nor the U.S. authorities have ever mentioned the eight women who also arrived in El Salvador. The same day they landed, without ever disembarking, they were sent back on a direct flight to the United States.

“The officers on the plane already had orders that they wouldn’t accept us. They told us we were in El Salvador, but that the women were going to be sent back,” says Franyeli.

To this day, there is no official explanation for why they were taken there or why they were sent back, though it’s known that CECOT is a men-only prison. The women — completely forgotten by the press and politicians — are now asking for help to seek justice for what was done to them.

“Deport her now, what they’re doing isn’t fair”

The family of 28-year-old Gladys Yoleida Caricote Tovar doesn’t know what to do or how to help their daughter. Since returning from El Salvador, she has been held in a detention center in Texas, where she was beaten a few days ago. “She called and said they hit her, she’s covered in bruises, they threw food in her face, and now she’s locked in solitary,” says a family member who asked to remain anonymous.

Gladys has been in ICE custody since December 10, 2024, when she was arrested in Colorado in front of her mother and her three young children. Within days, she was transferred to the Texas detention center, and her children were placed in foster care. Their grandmother was only able to get them back weeks later. On the day Gladys boarded the plane with the other seven women, she thought she was finally heading to Venezuela and leaving behind life in a cell. She couldn’t stand being locked up any longer. “She’s not well — she had a panic attack the other day and had to be taken to a doctor,” says the relative, who pleads: “They should deport her now; what they’re doing to her isn’t fair.”

That’s exactly what Yelitza wants for her daughter, who was also recently beaten at the detention center where she’s been held since returning from El Salvador. “My daughter doesn’t want to be in the United States anymore — she wants to be deported,” the mother says. “I don’t know what to do, where to go, or how to find her and bring her back. I just want her to come home. That country is so inhumane. She called me crying, said she couldn’t take it anymore, that she was going crazy.”

Of the eight women sent to CECOT, only three have been returned to Venezuela. The rest remain in detention centers, with no idea how long they’ll be held. Franyeli was deported on April 5, welcomed back by her father and children at the same home she had always known — the one she had hoped to fix up with money from her work in the U.S., so she could one day return and live in it again. Her husband Rolando remains incommunicado at CECOT to this day, and Franyeli doesn’t know how she’ll afford a lawyer to take on his case.

“It’s hard. I’m still processing everything, still waiting to hear from Rolando,” she says. In time, she’ll look for work and return to the life she had before leaving — the life she had once hoped would be different.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Comentarios