The election of John F. Kennedy as U.S. president in 1961, when little Robert Prevost was just six years old and growing up on the outskirts of Chicago, confirmed for the first time to American Catholics that one of their own could become the highest earthly leader in the country, after decades — centuries — of mistrust and prejudice. Now that helpful little boy from Chicago, who used to play at being a priest, has given his fellow believers another enormous boost. For the first time in history, the long-standing taboo that an American could never sit on the throne of St. Peter has been broken. Since Thursday, the former kid from the humble neighborhood of Dolton, on the outskirts of the Windy City, is Pope Leo XIV, the leader of the world’s 1.4 billion Catholics.

“It’s extraordinary,” says Dennis Carlotti, a practicing Catholic and lifelong resident near Dolton, who, like other residents, came to walk the streets where the new pope grew up after hearing the news of his election. “We were always told an American couldn’t be pope because the United States is already too powerful. And now someone from here, a kid from the parish next door, is our pope. It’s amazing.”

Chicago has been quick to claim its new favorite son. The White Sox stadium — the baseball team Leo XIV supports — has put up a large congratulatory sign for the new pope. The pizzeria where he would meet with family and friends on his visits proudly boasts of its eminent customer and has set aside the “Pope’s table.”

According to those who know him, Prevost’s childhood was a textbook example of the “American Dream” — the United States of the 1950s and 1960s, marked by the postwar baby boom and prosperity, the kind portrayed in TV shows of the era like Father Knows Best.

He was the youngest of three boys, nicknamed Rob or Bobby by his family. His father, Louis Prevost, was a school principal, and his mother, Mildred Martínez, was a librarian with some Creole blood and Spanish roots. They were a family of staunch Catholics: they attended Sunday Mass, and two of Prevost’s maternal aunts were nuns. The family lived in a modest one-story brick house. In Dolton in those years, fathers punched the clock at railroad companies or steel plants, mothers volunteered at school, and kids rode their bikes to their friends’ houses to play.

A calling from an early age

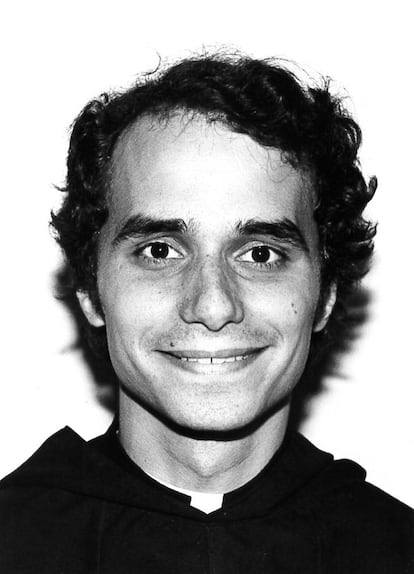

The future pope showed signs of his vocation early on. His brother John has said that as a very young boy he liked to play at being a priest and would use cookies to imitate the communion rite. When he was older, he became an altar server at his parish, St. Mary of the Assumption, where he also attended elementary school. He completed his schooling at an Augustinian boarding school in Michigan for boys who might be interested in the priesthood.

“We received a very good education and were invited to consider a life of priesthood,” recalls Father Bill Lego, who was his classmate at that school, and later at Villanova University, outside Philadelphia, at seminary in St. Louis, and during their theology studies back in Chicago.

In his teenage years, the future Leo XIV already showed “leadership ability,” thoughtfulness, and a “sense of humor,” says Lego, now pastor at St. Turibius Church in Chicago’s south suburbs. “He’s a very likeable person,” he adds, “I’ve never met anyone who found him unfriendly.” He’s a fan of tennis and baseball, and enjoys eating pizza when he returns during the summers to see his family, according to his brother John.

Prevost and Lego’s paths diverged when the future pontiff — “one of the smartest in the class, if not the smartest,” according to his friend — was chosen to continue his studies in Canon Law in Rome and to learn languages. In addition to English, he speaks Spanish, French, Portuguese, and Italian. The two would cross paths again as missionaries in Peru, where Lego was stationed from 1982 to 1993 and Leo XIV served at various times between 1985 and 2014, although they never worked together directly.

“He’s a very intelligent person who digests and retains information very well. He processes it carefully; he’s not someone who rushes into a decision. He deliberates a lot and prays a lot before making a decision,” says the priest. “He’s an excellent choice for pope.”

As head of the Catholic Church, Prevost “will focus on helping the poor and living the Gospels. He will also focus on building community. He’s an Augustinian pope, and we Augustinians are based on community life, sharing everything — the material things we use, but also our spiritual lives, our struggles, our joys,” Lego predicts.

In addition to his missionary experience, Prevost was also prior general of the Augustinians, a role in which he visited more than 50 countries. “He has experience with different styles of the Church in different parts of the world and knows different cultures,” says Lego.

A very different world

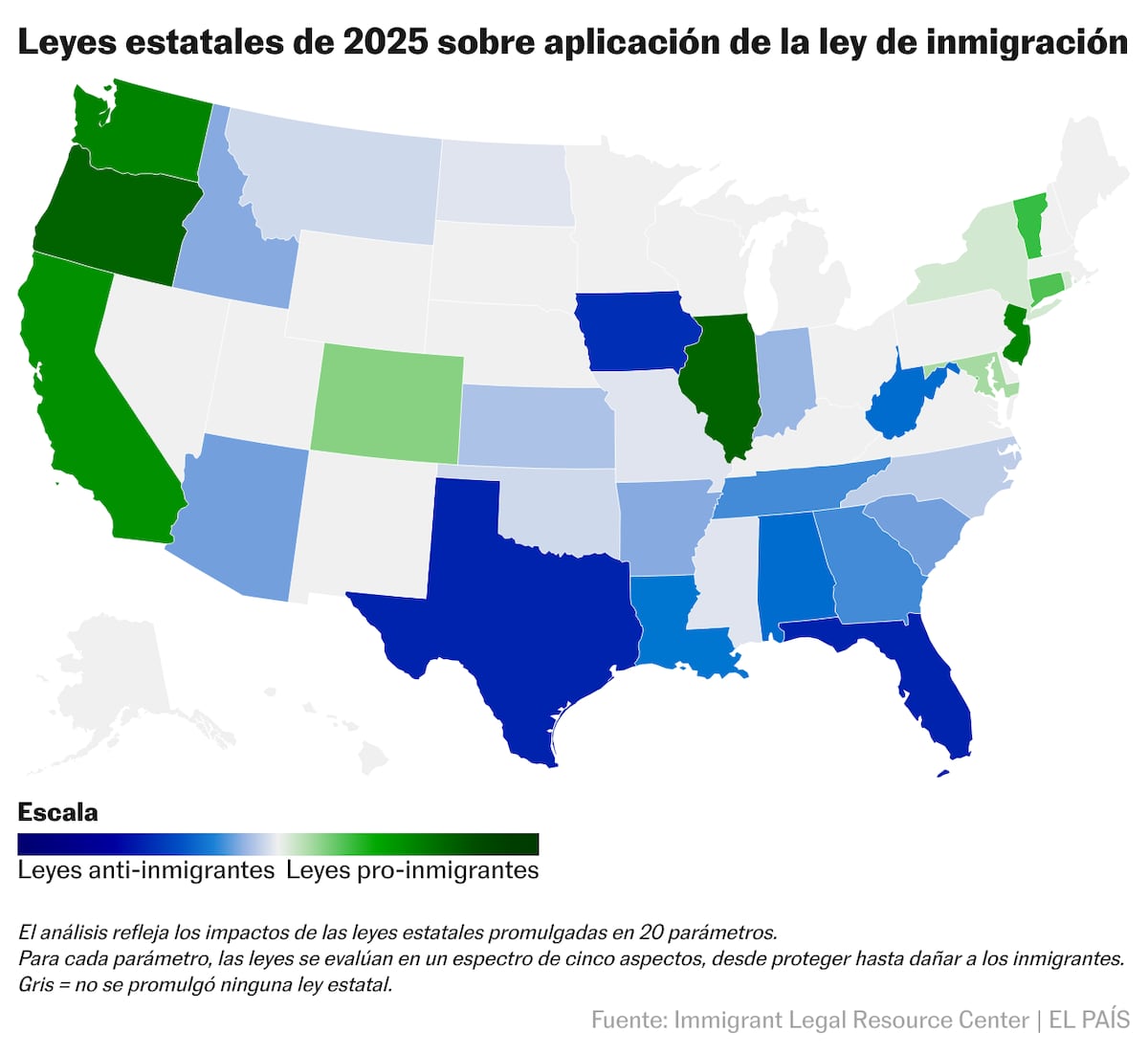

The world Prevost knew as a child has changed greatly. The new pontiff takes the chair of St. Peter at a time of serious international tensions, increasingly polarized politics and divisions on the issue of immigration, particularly within the United States. The Catholic Church’s global message is now at odds with the strong isolationism and protectionism trends spreading across the globe.

The neighborhood where he grew up is also very different. The white families that once made up more than 90% of the population have mostly moved to other areas. Now, the area is predominantly African American — 94% of residents — and Black pride flags hang from many streetlamps. In the Chicago metropolitan area, the Catholic faithful — 2.1 million out of nearly six million people — are no longer primarily of Polish, Italian, or Irish descent but increasingly include Spanish-speaking Latino communities. For many of them, the hardline immigration policies and mass deportations — criticized on social media, apparently, by Prevost before he even became Pope — are a daily nightmare.

The former Prevost family home — a modest one-story house that has not been owned by the family for some time — was up for sale last week, though the pope’s appointment has led its current owner to take it off the market, at least for now.

The old parish of St. Mary of the Assumption closed its doors 13 years ago and was sold by the archdiocese in 2019. Its land and facilities have changed hands at least three times. Its current owners are unclear what they want to do with it. One of them, Joe Hall, who was inspecting it this Friday, acknowledges that “any plan we had has just come to a standstill.”

Perhaps now it will be turned into a museum, like the birthplace of John Paul II. In the meantime, it has visibly deteriorated. The floor of the old school gym is sinking; the church pews are piled up in the former classrooms. A bird has taken advantage of what used to be a basketball hoop to build a nest. Where the tabernacle once stood, there is now a large spray-painted mural in red, blue, and orange; the confessionals have lost their doors; a large hole in the roof lets in rain and wind. Where a statue once stood, graffiti now reads: “Oh, My God.” Only the stained-glass windows remain intact, casting colorful light on the walls.

“It says a lot about the state of the Catholic Church in these parts today, doesn’t it?” says Carlotti, the neighborhood resident. “The makeup of society has changed. Parishes are closing, and one church now serves the role of three or four. Few people attend Mass anymore. Mostly the elderly.” He adds: “Hopefully, the Pope’s example will serve to give it impetus.”

That hope is shared by Father Bill, the pastor of St. Toribio, one of the priests who has seen his congregation gradually change. His community was originally Polish; today, it is mostly Latino. “Maybe, with the pope being from Chicago, more young people will consider a religious life. That can happen when there’s a connection — whether to the city or the country — and it could be a boost,” he says.

Chicago Bishop Lawrence Sullivan also shares these expectations. “The election of a new Holy Father has already brought new energy, and I would love for it to continue,” he says. “May it give us new opportunities to focus on God’s message, and that there are many more things that unite us than divide us.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Comentarios