France is perhaps the only Western country where a manifesto like the 2018 one would be conceivable, in which 100 women of culture, including Catherine Millet and Catherine Deneuve, backed the “freedom to bother,” criticizing the #MeToo movement and equating the liberation of speech it promoted with a puritanical and refractory “witch hunt” on sexual freedom.

The cultural sector and public opinion in France were again polarized two years later, when Roman Polanski was awarded the César for Best Director and actress Adèle Haenel walked out of the room shouting “Shame!” in protest at the honor bestowed on a filmmaker accused of raping a minor. Haenel herself had accused another director, Christophe Ruggia, of abusing her when she was 12 years old and making her film debut. Ruggia was sentenced to four years in prison for this crime last February.

Now superstar Gérard Depardieu has been sentenced to 18 months in prison after a lengthy trial during which he received public support from a number of actors, from Victoria Abril, Carla Bruni, Charlotte Rampling, and Fanny Ardant (who directed him in a film still being shot). This support, in turn, prompted a series of counter-stances, such as one signed by 70 prominent figures including actress Anouk Grinberg. The latter made a name for herself by being ejected from the courtroom where Depardieu was being tried after loudly expressing her displeasure with the statements made by the actor’s defense team.

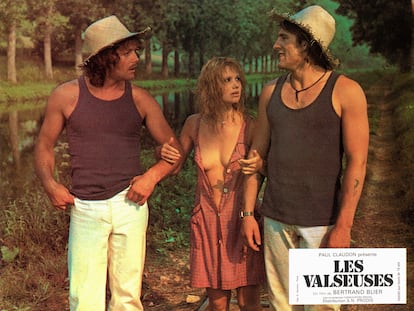

Grinberg has just published Respect, an autobiographical book in which she reveals having been sexually abused since childhood, as well as alluding to her traumatic experiences with director Bertrand Blier (who died in January of this year), who was her partner. Blier also directed her in three films, the last of which, Mon Homme (1996), featured her playing a prostitute, a role she initially refused, and which he allegedly forced her to take under the influence of tranquilizers prescribed by a doctor friend. These cases have brought a 1974 film, Les Valseuses (Going Places), back into the spotlight. In addition to being a huge box-office hit, it also polarized public opinion in a France that was, in theory, very different from today’s.

At the time, some considered it simply vulgar and esthetically worthless, but today, for reasons more closely related to its misogyny, it could lead many viewers to wonder how such a film could have existed in any era or country. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that it stars Depardieu, and that its director is none other than Blier, who was adapting his own novel for the screen. In any case, if there are any spatial-temporal coordinates within which something like Going Places was possible, it was those of 1970s France.

Phrases uttered in a jocular tone like “There’s an ass waiting for us somewhere,” or scenes like one in which a woman with a baby is forced to breastfeed two adults on a train (a situation she ends up enjoying), another in which the protagonist is thrown into a river after recounting her first orgasm, or one depicting an orgy with an underage virgin, all contribute decisively to the feeling of perplexity that it evokes today. “Thank you so much for everything!” the girl in question, played by a very young (and already superb) Isabelle Huppert, bids farewell to her abusers, thus inaugurating her reputation as a daredevil actress. Its title is also quite revealing, and in itself as disconcerting as any of the scenes described above: “valseuses” is a slang word for testicles.

But we were talking about context, and it’s important to place the film within it. Two weeks after its release in French theaters, President Georges Pompidou died, bringing to a close an era in French history characterized by a determined desire for economic progress and a social conservatism that followed the May 1968 revolts. Going Places, with its nihilism and deliberate vulgarity, seemed to dynamite both the revolutionary project of May 1968 and the righteous spirit of Pompidou, heir to the Gaullism against which the young 1968ers had revolted.

Other films of the time, such as Last Tango in Paris (Bertolucci, 1972), The Mother and the Whore (Eustache, 1973) or The Big Feast (Ferreri, 1973), which were very different from each other, nevertheless started from similar intentions. But Going Places was the perfect counterpoint to the other great French hit of the year, Just Jaeckin’s Emmanuelle, which played in the same league of lucrative scandal, from opposite esthetic and political premises. If Emmanuelle was all about the mischievous transgression of sexual mores as a means of consolidating the bourgeois order, in Going Places, it was more about subverting that order, even if only in appearance.

Another thing both films have in common is that their plots are not particularly complex. Going Places follows the adventures of two petty criminals who go around committing small-time thefts and harassing every woman who crosses their path, including an anorgasmic hairdresser who, for reasons that defy explanation, decides to join them and form a threesome that plays out in every possible way.

For his second film, Blier worked with two promising actors who, at 25 years old, were just starting their careers: Depardieu, fresh out of an adolescence and early youth spent skirting the edges of crime, and Dewaere, already leading a tragic life that would come to an end eight years later in the worst possible way (by which point he had become the best French actor of his generation). Alongside them were Miou-Miou, Dewaere’s partner and another discovery, and the veteran, highly respected Jeanne Moreau — the only famous name in the cast — who lent the production a touch of prestige with her unsettling role as a mature woman who, upon being released from prison, decides to take her own life after sleeping with the delinquent duo.

The film’s ugly aesthetic was in keeping with its unusually coarse language. If writers like Rabelais and Céline — figures associated with the film — but also Pasolini, Genet, Bataille, or Barthes, have shown how bad taste and the abject can serve as destabilizing or even revolutionary tools, in Going Places, Bertrand Blier carried out this project with undeniable diligence.

Against all odds, the film was a box office hit in France: it became the second highest-grossing domestic release in the country, selling nearly six million tickets, and was distributed internationally. But, as might have been expected, the critics were deeply divided. In Écran magazine, Jean Domarchi called it pornographic, adding: “I’ve seen, by circumstance, other pornographic films, and I must say none have struck me as so nauseating as Going Places.” In Le Monde, Jean de Baroncelli argued that its sense of humor and “human warmth” redeemed it from its potential sins. Upon its release in the United States, Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote: “It’s a movie whose good performances and technical expertise can never disguise the vacuity of its assumed nihilism, which bears about as much relation to the real thing as fashion photography does to the work of Cartier-Bresson.”

In Spain, however, where it premiered in 1977 — after the death of the dictator Francisco Franco — Fernando Trueba praised its “aggressive vitality” and remarked that “few films present sex in such a natural, unselfconscious, and hilarious way.” What is surprising, as noted by Libération in a recent article, is that the film did not at the time provoke many accusations of misogyny; its critics focused primarily on its violence, vulgarity, or obscenity. It is only over time that such there has been debate about its representation of women.

In truth, Going Places was only a prelude to the far more radical provocation Blier would stage in his next film, Calmos (1976), the story of two men, weary of being victims of female empowerment, who choose to live as incels avant la lettre — until they are captured and abused by feminist militias. As with Going Places, Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) was one of its dystopian influences. But the original spark came from the U.N.’s declaration of 1975 as the International Women’s Year, which Blier responded to with a satirical take on what he saw as the supposed excesses of feminism. The rest of his filmography (including the somewhat tamer Get Out Your Handkerchiefs, which won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film in 1979) would explore variations on the battle of the sexes in a nihilistic register reminiscent of Marco Ferreri — though Blier was intellectually and formally less refined than the Italian.

When Blier passed away earlier this year, tributes in the French media coincided with renewed debate over whether films like Going Places should still be shown in cinemas or on television in today’s world.

On the radio station Europe 1, Miou-Miou defended the film but also spoke of the “humiliating” methods she had been subjected to by the director. Brigitte Fossey — known to French audiences since childhood thanks to René Clément’s movie Forbidden Games — who played the young mother assaulted on a train in Going Places, admitted she could no longer bring herself to watch her scene, which she described as “horrible, horrible, horrible.”

Geneviève Sellier, professor at the University of Bordeaux and a leading scholar in film studies with a focus on gender and sexual identities, described the film as “an apology for masculinism in its most vulgar and provocative form.” In a conversation related to the Depardieu case, Sellier remarked that Going Places reflects “the era’s tolerance of rape culture,” just as Tenue de soirée (Evening Dress) (1986), another of Blier’s hits, was in her view “an outright apology for rape” as well as “a display of obscene masculinity where women are not needed” (in that film, a love triangle devolves into a relationship between two men, one of whom cross-dresses).

Later, it would be the director himself who came under scrutiny, particularly in the autobiographical book by Anouk Grinberg, his partner during the 1990s and mother of his son Léonard. In 1996, Grinberg won the Best Actress award at the Berlin Film Festival for Mon homme, directed by Blier, in which she portrayed a classic male fantasy: the happy prostitute who is also madly in love with her pimp.

In her book, Grinberg writes: “If people watch Mon homme, I want them to know it’s a film about torture. I didn’t want to do it. Blier […] welcomed me into his world with such enthusiasm that I thought it was love. In reality, he was an ogre. Very quickly, I became his thing, his muse. Being the muse means being the object of a man’s delusions. It means being surrounded by a man’s gaze, which turns you into his fantasy. And you’re not allowed to be anything else.”

There has been no shortage of voices, in this case as in others, lamenting that “these days you can’t say anything anymore” — especially since Going Places was recently remade in the U.S. by John Turturro, albeit in a far less offensive tone. It’s fair to admit that some of what Going Places expressed in the world of yesterday can no longer be said in today’s. But in exchange, many other things can now be said that were once unimaginable: a film like Baise-moi by Virginie Despentes and Coralie Trinh-Thi (which, incidentally, is now 25 years old, making it equidistant from Blier’s film in time) completely reverses the sexual power dynamic — and in 1974, it would never have reached commercial theaters under any circumstances.

The real issue is choosing what we want to say, and why we want to say it. And also studying what the things that were said in a given time reveal about that moment in history.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Comentarios