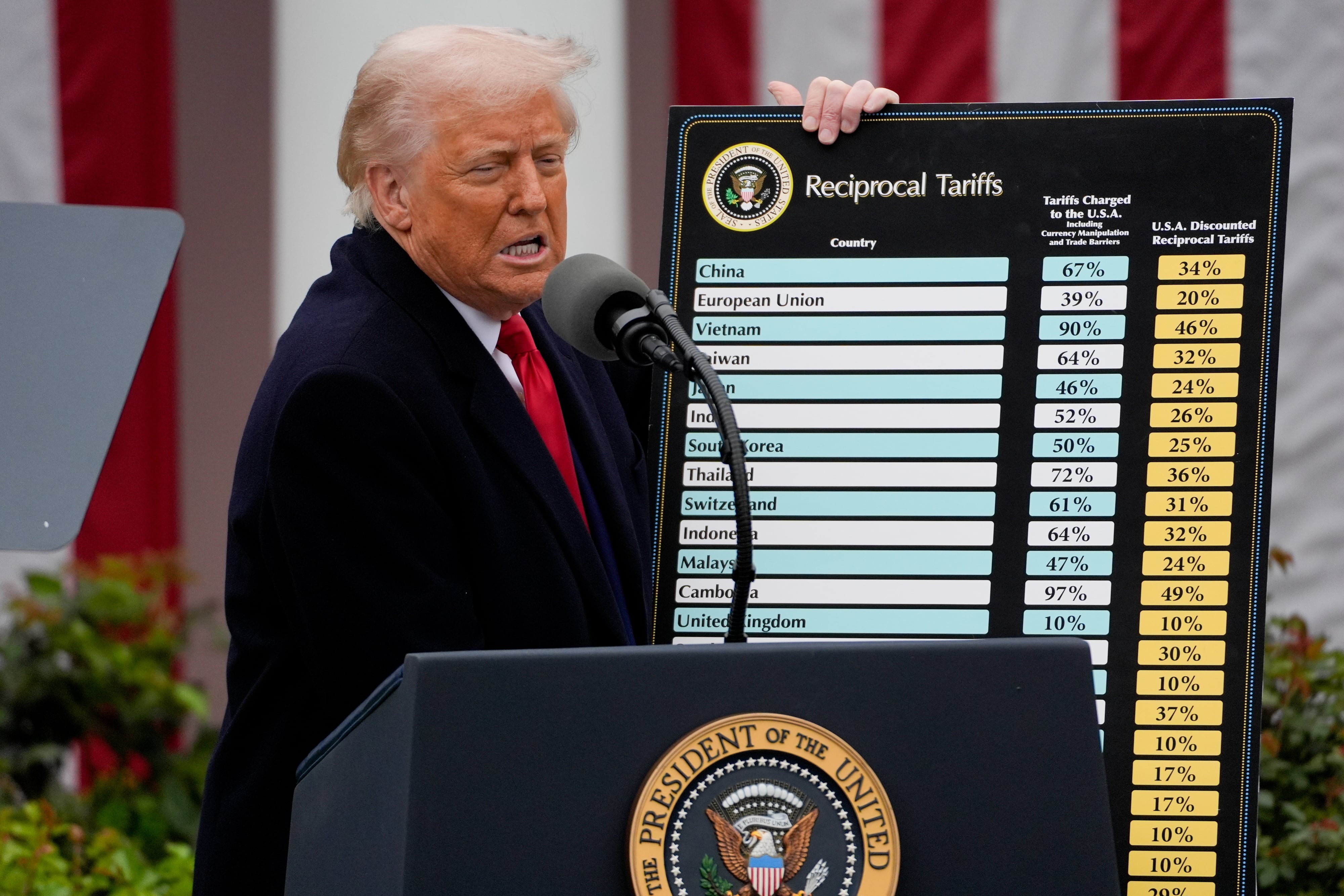

The tariff war launched by U.S. President Donald Trump against the rest of the world has had numerous negative consequences for the world’s largest economy: widespread declines on Wall Street, a worrying deterioration in the U.S. debt market, a weakened dollar, a downgraded growth forecast by the IMF for this year, and retaliatory tariffs imposed by other countries.

Despite this string of bad news, the White House is desperately clinging to announcements — or even just signs of intent — from companies across various sectors to increase their production capacity in the U.S. in order to avoid Trump’s tariffs. These decisions are portrayed as triumphs by the Trump administration, but experts point to their collateral damage: rising costs and a heavier burden on American consumers’ wallets. Battles won in the midst of a war with a bleak outlook.

The list of companies that have decided to bow to Trump is diverse: from Japanese automaker Honda to Italian liquor maker Campari, French luxury brand Louis Vuitton, and Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche. Honda recently announced it would move production of the hybrid version of its popular Civic model from Japan to the U.S. Campari and Louis Vuitton have expressed interest in expanding their production capacity in the country, while Roche announced a $50 billion investment over the next five years.

“These announcements aren’t just short-term reactions by companies — they’re about avoiding the impact of Trump’s tariffs or those of a future president like Vance,” explains Rafael Pampillón Olmedo, professor of economics at CEU San Pablo University in Spain. It’s a strategy companies use “not only to reduce immediate costs, such as tariffs, but also to adapt to an increasingly protectionist trade environment.” Still, Pampillón warns of the consequences: “This could lead to a complete reshaping of supply chains.”

Manuel Alejandro Hidalgo, professor at Pablo de Olavide University in Seville, is surprised by the hasty moves from these firms, considering Trump’s erratic behavior. “Someone who says one thing one day and the opposite the next doesn’t seem like a reliable gamble — especially when the cost of opening certain types of factories in the U.S. is so high,” he warns.

Hidalgo questions whether these relocations will truly benefit the companies, even if they avoid tariffs, and notes that it will ultimately be U.S. consumers who bear the burden of higher product prices. “There’s overwhelming empirical economic evidence pointing in the same direction: tariffs lead to inflation. What the U.S. is doing is shooting itself in the foot, no matter how much it tries to spin these moves as successes,” he concludes.

Not all expert voices are as critical. “The current situation is highly uncertain, since we still don’t know the final tariffs that will be imposed on other regions, or what tax incentives the government plans to introduce. Several companies have already announced plans to open new facilities in the U.S. — for example, Nvidia will manufacture its Blackwell AI chips in the country for the first time, in partnership with TSMC, and is already building facilities in Texas with Foxconn,” explains Adam Miquel, director of alternative investments at Aurica Capital.

He argues that reshoring will benefit sectors such as electronic services, with the potential opening of hundreds of data centers that require access to the power grid and specialized module installations. In March, TSMC announced a $100 billion investment to produce chips in the U.S., on top of the $65 billion previously pledged during Joe Biden’s presidency.

These chip investments have been boosted by the subsidies, deductions, loans, and guarantees provided under the 2022 CHIPS Act, which Biden signed to ensure domestic semiconductor production. Micron, Samsung, and Intel have also benefited from these incentives for new plants and R&D.

Biden also promoted industrial growth through the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which allocated roughly $750 billion to lower healthcare and energy costs, promote clean energy investments, and strengthen the IRS workforce. The act also projected the creation of up to 1.5 million new jobs and a 0.88% GDP increase by 2030.

Domestic companies like Ford used these incentives to build three new electric vehicle battery plants in Stanton, Tennessee, and Glendale, Kentucky. While Biden’s strategy focused on subsidies and the market’s attractiveness, Trump’s is centered more on imposing tariffs.

Job creation

According to Roche, once all its new manufacturing capacity is operational, it will export more medicines from the U.S. than it imports — although it noted that its diagnostics division already runs an export surplus from the U.S. to other countries. The company stated that these investments will strengthen its already significant U.S. presence, which includes 13 manufacturing sites and 15 R&D centers.

“These investments […] are expected to create more than 12,000 new jobs, including nearly 6,500 construction jobs, as well as 1,000 jobs at new and expanded facilities” said Roche. The company has a workforce of over 25,000 people spread across 24 sites in eight states: Kentucky, Indiana, New Jersey, Oregon, Arizona, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and California.

Two days after the announcement, Roche CEO Thomas Schinecker reiterated the company’s new U.S. focus during a presentation to investors and analysts, reminding them that the company has invested $67 billion in the country over the past decade. In fact, the U.S. market accounts for 52% of the pharmaceutical division’s revenue — the group’s largest unit. In the first quarter, U.S. sales grew by 6%. Company sources told EL PAÍS that these investments align with Roche’s long-term strategy of “being where our customers are” and where patients need them.

Novartis also recently announced a $23 billion investment in the U.S. The Swiss pharmaceutical company plans to build six new manufacturing plants, some of which will produce pharmaceutical ingredients, along with a new R&D center in San Diego, California. These facilities will be built over the next five years and are expected to create 1,000 specialized jobs — such as for engineers and scientists — as well as 4,000 additional positions for staff and construction workers. The company has yet to decide the location of four of these plants, but two — focused on developing cancer therapies — will be built in California and Texas.

Within this trend, Eli Lilly announced in late February — amid Trump’s tariff offensive — a $27 billion investment in new U.S. plants over the next five years.

In the automotive sector, in addition to Honda, other companies have been forced to rethink their supply chains and regional production. For instance, the Volkswagen Group has halted shipments of cars by sea and land to the U.S. for brands like Audi. The Audi brand sells a lot in the U.S., especially the Q5, a model assembled in Mexico. According to Reuters, the premium brand now intends to build its best-selling models for the U.S. market at a local factory, the location of which it will announce this year.

BMW, meanwhile, was the largest automotive exporter from the U.S. last year thanks to its plant in Spartanburg, South Carolina — with 225,000 sport and coupe vehicles exported, worth over $10 billion. Even so, the German company announced in April that it will boost production at that facility by 80,000 units annually.

Mercedes-Benz, the other major German automaker, does not produce any vehicles in the U.S., though it does in Mexico. According to Reiner Hoeps, president of Mercedes-Benz Spain, the company is monitoring the situation and considering several scenarios, including the possibility of manufacturing in the United States.

“In recent months, we’ve been selling like crazy in the U.S. due to an anticipation effect. Cars that weren’t affected by the 25% tariff were being sold. But once the current stock runs out, we expect a slowdown. Combining both effects, we estimate U.S. deliveries will decline slightly — around 3% to 5%. The impact will be much greater in 2026 if tariffs remain in place,” the executive noted.

Teknia, a Spanish automotive components manufacturer, told EL PAÍS that it is seeking “opportunities” to grow in the U.S. by acquiring other companies or production assets. The firm already operates a factory in Nashville, Tennessee, and has visited other companies as potential acquisition targets.

“Although nothing is concrete yet and no deals are underway,” Teknia noted, it emphasized that its strategic plan already included growing the business in North America — “and now, due to the tariffs, especially in the United States.”

In any case, the move toward increased local production to replace imports will likely lead to higher prices for both businesses and consumers, warns economist Pampillón.

He explains: “Imported products and components will be more expensive; new production in the U.S., protected by tariffs, will come from less efficient companies and thus incur higher costs; and U.S. companies, seeing reduced foreign competition due to tariffs, will seize the opportunity to raise their prices and boost profits. In short: more inflation,” the professor concludes.

Still, he adds: “In the long run, the arrival of foreign companies in the U.S. could yield significant benefits for the country in terms of job creation and strengthening of its production infrastructure.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Comentarios