José “Pepe” Mujica has died. This time, at 89, he decided it was time to go, as announced on Tuesday by Uruguay’s president, Yamandú Orsi, on social media. “This is as far as I go,” Mujica had said back in January. But it wasn’t so easy for him to leave us behind. Not 50 years ago either, when he was shot six times. Nor during the 10 years he spent locked up by the military in a pit barely one square meter in size.

The first time, 12 liters of blood saved his life. The second, he tamed frogs and fed mice to avoid going insane. He emerged from that cell wiser, he used to say, and returned to what he knew: politics. In 1994, he was elected deputy for Montevideo; in 1999, senator; and in 2010, president of Uruguay with nearly 55% of the vote.

Mujica captivated the world as a symbol of austerity and simplicity, a rare kind of leader, who, near the end of his life, voiced warnings tinged with pessimism, yet never lost faith in humanity. “I dedicated myself to changing the world and I didn’t change a damn thing. But I was entertained,” he told EL PAÍS in November, worn out from the radiotherapy sessions he was undergoing to treat his cancer. “And I gave meaning to my life. I’m going to die happy. I spent it dreaming, fighting, struggling. They beat me up and all that, but it doesn’t matter, I don’t have debts to pay.”

A survivor of countless battles, Mujica ultimately lost the war to cancer — first in his esophagus, then in his liver. When the metastasis was confirmed, he was exhausted and decided to throw in the towel.

“I was given 31 shots [of radiation] at 7 a.m. every day. They beat down the cancer, but they left me with a hole like this,” he told EL PAÍS last year, tracing a circle the size of an orange with his fingers.

The side effects of the treatment made it difficult for him to eat, and he felt weak and tired. Three months ago, he made his final public appearance at the campaign closing event for his chosen presidential candidate, Yamandú Orsi, who would go on to defeat the right in a runoff election held on November 24.

In those days, Mujica was elated: he was passing the torch of his political legacy to a younger generation, urging them “to live with simplicity, because the more you have, the less happy you are.”

José Alberto Mujica Cordano — that was his full name — was born in 1935 in Paso de la Arena, a rural neighborhood on the outskirts of Montevideo. His mother was a horticulturist, and his father, a small rancher, died in poverty in 1940, when Mujica was just six years old. By the age of 14, the young Mujica was already taking to the streets, demanding better wages for the workers in his neighborhood.

In 1964, he joined the guerrilla group Movimiento de Liberación Nacional-Tupamaros. He was imprisoned four times and escaped twice — once in a legendary breakout in September 1971, when 106 guerrilla fighters tunneled out of the Punta Carretas prison in Montevideo after months of digging.

He was eventually recaptured, and in 1972 became one of the military regime’s “nine hostages”: key Tupamaro leaders who were told they would be executed in prison if their organization resumed armed struggle.

The 2018 film A Twelve-Year Night, directed by Álvaro Brechner, depicts Mujica’s years in that military prison alongside fellow guerrillas. “We had to fight against madness, because in that kind of prison, the goal was to leave us mentally broken. And we won: we didn’t go mad,” he said at the film’s premiere.

He often recalled the struggle to stay connected to life in the cell, where he could barely move. “I was locked up for seven years in a room smaller than this one. Without a book, without anything to read. They took me out once a month, twice a month, to walk around a courtyard for half-an-hour. Seven years like that,” he said in his final interview with this newspaper.

“To keep myself sane, I began to remember things I had read, things I had thought about when I was young. When I was young, I read a lot. Later, I dedicated myself to changing the world and I didn’t read anything. I couldn’t change the world, but what I had read when I was young helped me,” he continued. “I talk to the person I carry inside me — the one who rescued me when I was imprisoned, when I was alone. I start to remember and remember and remember.»

Mujica did not emerge unscathed from that cell. He became seriously ill with a bladder condition and ultimately lost a kidney. But he survived. In Mujica, a biography written by Miguel Ángel Campodónico, the former president recalled his time in the military prisons, but without playing the victim. “I’m not one to talk about torture and how badly I suffered. In fact, it even annoys me because I’ve seen a kind of race measured by a ‘torture meter.’ People who take pleasure in repeating, ‘Oh, how badly I suffered.’”

His critics reproached him for not doing enough as president to prosecute the military responsible for the disappearances and torture during the dictatorship. Mujica responded that he had decided not to “get even.”

“In life, there are wounds that have no cure, and you have to learn to go on living. I know that there are people who won’t support me, but I’ve chosen a more intelligent and less sentimental position. That’s why I didn’t use power to go after the military. If I’m going to try to get even… God forbid,” he told EL PAÍS.

Nevertheless, Mujica always saw those years as the ones that most “shaped” his way of thinking. “The need to exist makes one think and rethink and ask questions that are rarely asked in everyday life,” he often said.

Out of those questions — and the answers he found — was born the Mujica who captivated the world: a leftist politician who made himself heard from a small South American country. He arrived at his first day in the Senate on a motorcycle, dressed in street clothes, coming straight from his small farm in Rincón del Cerro, about a half-hour’s drive from Montevideo. He lived there — surrounded by vegetable crops, his three-legged dog Manuela, and farm animals — from the time he was pardoned in 1985 until his death.

It was in that rural refuge that he took his commitment to frugality and simple living to the extreme. He never got off his tractor or out of his light blue 1987 Volkswagen Beetle, even when he was president. Anyone who wanted to interview him had to get their feet dirty — whether heads of state like Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva or royalty like Spain’s King Juan Carlos I, whom he received in 2015 just hours after leaving office. “They say I’m a poor president. Poor are those who need a lot. I learned to travel light,” he told Juan Carlos with a laugh. “You can’t — because you had the misfortune of being born a king.”

Mujica often pushed back against being labeled “the world’s poorest president.” “This is my world — neither better nor worse, just different,” he once said, referring to the perspective taken by the documentary El Pepe, A Supreme Life, by Serbian filmmaker Emir Kusturica.

“The key lies in morality,” he told EL PAÍS in November. “The problem is that we live in a consumerist era, where we think that succeeding in life is buying new things and paying the mortgage. We’re building self-exploited societies. You have time to work, but not to live.”

That’s why he had this message for young people: “You’re free to do what you want with your life, which is sometimes just nonsense. Do you understand? Because culture is the daughter of nonsense.”

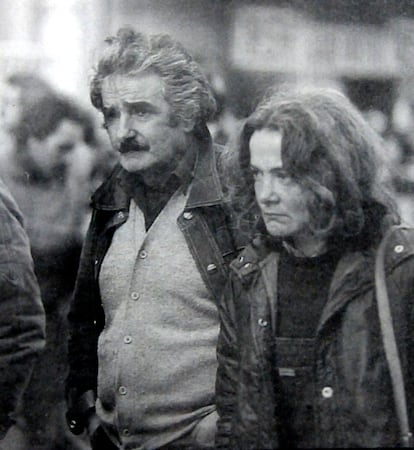

From his years as a guerrilla fighter came his relationship with Lucía Topolansky. They met during a clandestine operation when he was 37 and she was 27. During their years of imprisonment, they exchanged only a few letters, and it wasn’t until 1985 — after the return of democracy — that they were finally reunited. They remember little from those years, she once said, because “it’s a bit like those wartime stories, where human relationships are distorted by the circumstances — you’re on the run, you could be arrested, you could be killed. It doesn’t follow the parameters of a normal life.”

Topolansky entered the Senate in 2005 with the Frente Amplio (Broad Front), and in 2010 she had the honor of placing the presidential sash on her husband, a recognition earned by being the most voted legislator. Seven years later, she became vice president under Tabaré Vázquez. Mujica and Topolansky were never apart.

“At every age, there’s a scale of feelings. When you’re young, love is volcanic. When you’re old, it’s a sweet habit. If I’m still alive, it’s because of her,” Mujica said shortly before his death.

His first speech as a senator in 2000 was dedicated to cows. In 2005, he became Minister of Livestock under then-president Tabaré Vázquez. And once in office as president, he proposed a national debate on the ownership of large estates and suggested solving the rural labor shortage by “importing” farmworkers from neighboring countries. He also championed a bold progressive agenda that placed Uruguay at the forefront of the region: he legalized abortion and same-sex marriage, and regulated the production and sale of marijuana. Suddenly, the world turned its attention to Uruguay.

Back in November, Mujica recalled his time in office by mentioning his relationship with Barack Obama, “an intelligent guy who saw problems as they were.” But above all, he spoke most fondly of his deep friendship with Lula da Silva, whom he regarded as a “world figure.”

In 2018, Mujica finally stepped away from active politics. He resigned from his Senate seat with a letter addressed to the president of Congress — his own wife — in which he cited “personal reasons and fatigue from a long journey.” Even so, he continued to support the Broad Front and to speak out on current events to anyone who wanted to listen. When he learned he had cancer, he vowed to fight, but it was clear he had become weary.

Until the end, Mujica made it clear he did not seek a place in history’s bronze statues. “Men don’t make history — we make comic strips,” he said in one of his last interviews. “Why? Because in the vastness of the universe and time, we are too full of ourselves. This business of creating a god in human form and everything that goes with it is an old atavism.”

Before he died, Mujica asked not to be approached for more interviews. “My cycle is over. Honestly, I’m dying, and the warrior has earned his rest,” he told the weekly Búsqueda. He announced his decision to die at home, on his farm, and to be laid to rest “under the big redwood” where he buried his three-legged dog Manuela in 2018. “And that’s it,” he said — and that was how he chose to leave this world.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Comentarios