When cruise ships dock in Juneau, Alaska’s capital, the tourist invasion causes the fragile internet signal to become unstable for the residents. That’s why, on Monday, May 5, someone had to tell Tessa Hulls that her graphic memoir, Feeding Ghosts (2024), had become only the second comic in history to win a Pulitzer Prize. In 1992, Art Spiegelman’s masterpiece, Maus — based on the memories of his father, a Holocaust survivor — was awarded a Special Citation.

Hulls was working as a cook at the Alaska Capitol’s cafeteria. It’s a seasonal job; it lasts as long as the legislative session. And, she says, it allows her “to step back from the burnout of being a full time freelancer.”

“Sometimes,” she adds, “you need [some] structure.”

It was a state representative who told her about the prize — worth $15,000 — that she hadn’t expected. She barely had time to process the news: there were still plenty of sandwiches to prepare.

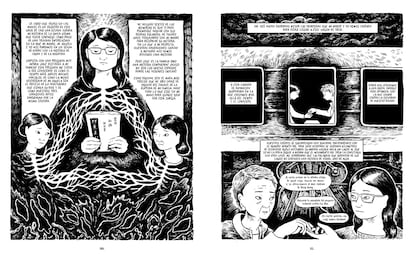

Feeding Ghosts has been racking up comic book awards since it was published a year ago in English, but the Pulitzer Prize is something else entirely. Hulls’ graphic work competed with standard autobiographies and memoirs. And yet, the jury deemed the nearly 400-page graphic novel — full of dense black-and-white drawings, quotes, and narrative insights — “an affecting work of literary art” and “a vivid, heartbreaking journey into history that exposes the fear and trauma that haunt generations.”

In the book, Hulls climbs her family tree to delve into her past and the history of China, where her grandmother and mother were born. Sun Yi is the grandmother: a journalist from Shanghai who escaped to Hong Kong as a single mother. In 1957, she published a successful memoir about her years under Mao’s rule. It was written in a three-month-long sitting, amid a state of feverish paranoia. Afterward, Sun Yi checked herself into a sanatorium. “She lost her mind and never found it again,” her granddaughter writes.

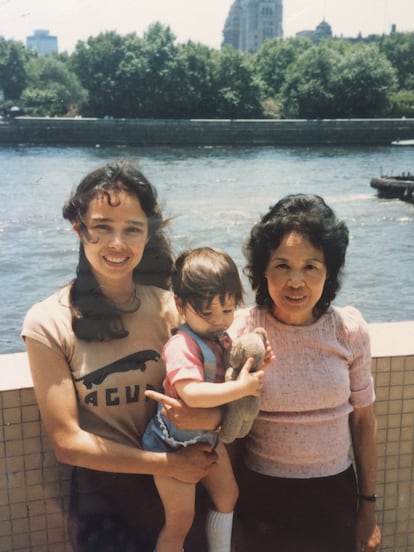

Her mother’s name is Rose. After studying at an elite school for European expatriates, she brought the family to the United States in 1970. In 1985, she gave birth to Tessa, who grew up in a tiny town in Northern California with the ever-present “ghost” of her grandmother, who would die in 2012. “[She was] the 90-pound specter who shuffled around our house in gray Costco sweatpants,” Hull writes.

They were separated not only by madness, but also by language: the granddaughter never learned Mandarin. And, in the comic, she recounts how, as a teenager, she loudly chose “to be American rather than Chinese.”

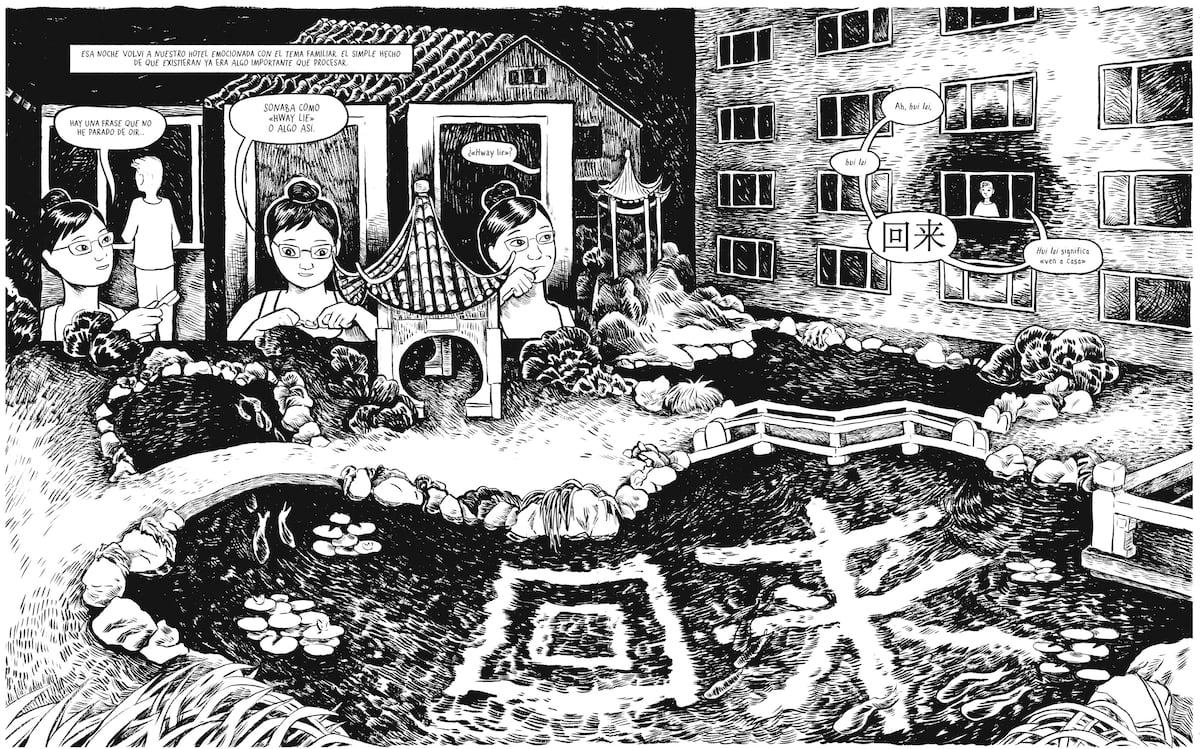

The idea behind the project was to address the fractured relationship between her mother and grandmother against the backdrop of the 20th century. “I thought it was just going to involve learning about Chinese history,” the author explained, on Friday, May 9, in a video interview with EL PAÍS from Juneau. But when she had Sun Yi’s memoir translated — and after she read it for the first time — things changed. “I realized that the story was much more complicated and much more emotionally nuanced.”

Studying Mao

She spent the first four years of the project “researching.” And not only did she have to learn history and some Chinese… she also had to learn how to write a graphic novel. Because one thing was clear from the start: that would be the language her story required.

In the end, Hulls came to another conclusion: she doesn’t plan on publishing another book.

When she started Feeding Ghosts, Hulls wasn’t even interested in comics as a medium. She had primarily dedicated herself to painting, although her colorful style is absent in the graphic memoir. She had also embarked on varied adventures: working as a cook in Antarctica, painting murals in Ghana, or cycling the 3,000 miles between Southern California and Maine to escape an impending marriage.

“I grew up reading Calvin and Hobbes. And that was the first thing that made me want to be an artist,” Hulls recalls. With Fun Home (2006) — the unforgettable tragicomic graphic memoir, with which Alison Bechdel settled scores with her father — she saw, for the first time, “the potential of that format.”

“That’s when I started teaching myself in my 30s. ‘What is this medium? How does it work? What are its rules?’ And that was actually really fun, just getting to devour a lifetime’s worth of graphic novels in just like a huge, rich meal over the space of a couple years.”

In addition to comics, Hulls read every Chinese history book she could find. “And then I would go to the bibliography and I would look up those books,” she adds. She also contacted experts, historians, and journalists. They helped her with the comic, which incorporates endnotes like an essay.

Her great effort to understand the past is evident: the result can also be read as a lesson about the turbulent 20th century in China and Hong Kong. Hulls only requires a handful of meticulous drawings to effectively recount Mao’s Great Leap Forward, or the life of the European-Asian community six decades ago in the British colony. She researched the latter subject matter to understand more about her grandfather’s circumstances: he was a Swiss diplomat who abandoned Hulls’ grandmother after getting her pregnant.

The writing and drawing process — which consumed “about 80 Japanese nylon-tipped brushes” — took another four years, including six months isolated in a cabin in the middle of the woods in Oregon, thanks to the Margery Davis Boyden Wilderness Writing Residency. “That’s where I found the structure of the story,” she recalls.

In the comic drama Are You My Mother? — the 2012 book that followed the phenomenal success of her best-known work — Bechdel also wrote about her mother while she was still alive. “You could see the ways in which […] she was afraid of the level of honesty it would have required for that book to be as transcendent as Fun Home‚” Hulls explains. “So, I think I learned a lot from [her second work], but maybe more in the sense of what doesn’t work.”

Like the aforementioned graphic drama, Feeding Ghosts is also (or above all) the story of a mother-daughter relationship, with its arc of guilt, blame and reconciliation. Together, Tessa and Rose traveled to China and Hong Kong as part of Tessa’s research process. The author notes how her mother was present throughout the process.

“How do you tell a story about someone who is still alive and in your life and who can be harmed and hurt by your words? When I was doing revisions, I would look over all my pages and the question I would ask myself is: ‘Where can I place more compassion?’”

“I was very cautious [about] only giving her [pages] that felt like they were finished, [so that] she could really see what I was going for. [But] with her dementia, unfortunately, she couldn’t read the whole thing by the time it was done,” the author laments.

In the memoir, Hulls portrays herself as a kind of cowboy. She’s driven by an appetite for “the American frontier.” She embodies that indomitable spirit, which has taken her to six continents and made her divide her life between Seattle and Alaska. By growing up in a small town “in the middle of nowhere,” she has seen everything through the lens of one of her mother’s favorite phrases: “I don’t understand this American culture.” The lack of role models and the invisibility of Asian culture in contemporary television and film didn’t help, either. Only recently has the dominant narrative in the United States embraced a different perspective, with successful productions like the Oscar-winning Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022). This film — another story about the relationship between a Chinese-American mother and daughter — is one of Hulls’ favorites. She confesses that she can’t help but cry every time she watches it.

This opening of the canon has also brought about “an enormous and vicious backlash,” especially from Donald Trump’s entourage. “[This] subset of people feels very threatened by the fact that this really cookie cutter white model of America is [perceived as] being threatened and overrun.”

Her study of Maoism, she adds, has given her “context to understand what’s happening in the United States.” She points out that “the banning of language, the list of words that can no longer be used [is very similar to] a specific period of Chinese history. It’s so similar to what Mao and the communists did when they came to power: ignoring reality and trying to impose a narrative.”

When asked if winning the Pulitzer had changed her mind about retiring from literature, Hulls is blunt… much to the dismay of her publisher, MCD Books. “No, no, I’m not doing it. I think the process of working on this book really made me understand the difference between being an author and being a multidisciplinary artist. And I’m definitely a multidisciplinary artist.”

She’s content that the award will lead Spiegelman — with whom she now shares a special place within the Pulitzer Prizes — to read Feeding Ghosts. She believes that their books “are very much in conversation with one another.”

Hulls’ entry into the select club of awards primarily associated with great American reporting may help her with her next venture: she wants to dedicate herself to comics journalism. And she wants to do this from Alaska, where “so much is going on at the complicated intersections of climate change, environmental justice, Indigenous sovereignty, and resource extraction.”

Until that’s possible, she’ll continue making sandwiches for the state legislators.

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Comentarios