[ad_1]

Originally from Bayamón, a town west of Puerto Rico’s capital San Juan, Miguel Ángel Amadeo arrived in New York at the age of 13 with his mother. It was 1947, and more than 70 years later Amadeo is not only still in the city but has become a living legend. He is the owner of an emblematic and unique music store — the oldest in New York.

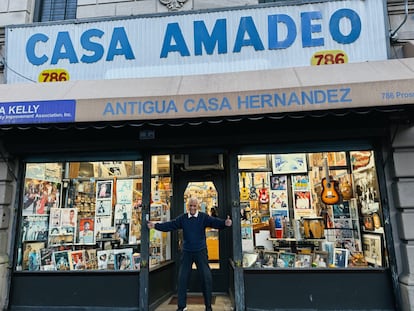

Stepping into Casa Amadeo, also known as Antigua Casa Hernandez, at 786 Prospect Ave in the Bronx, is like taking a one-way ticket to Puerto Rico — and, more than anything, to the history of Latin American music in the Big Apple. But above all, it’s a way to spend time with Amadeo, one of the behind-the-scenes stars who helped weave what New York’s Hispanic-rooted music is today. Although his given name is Miguel, everyone knows him as Mike — a name he adopted when he moved from his native island to Manhattan, since it was easier for his teachers to pronounce.

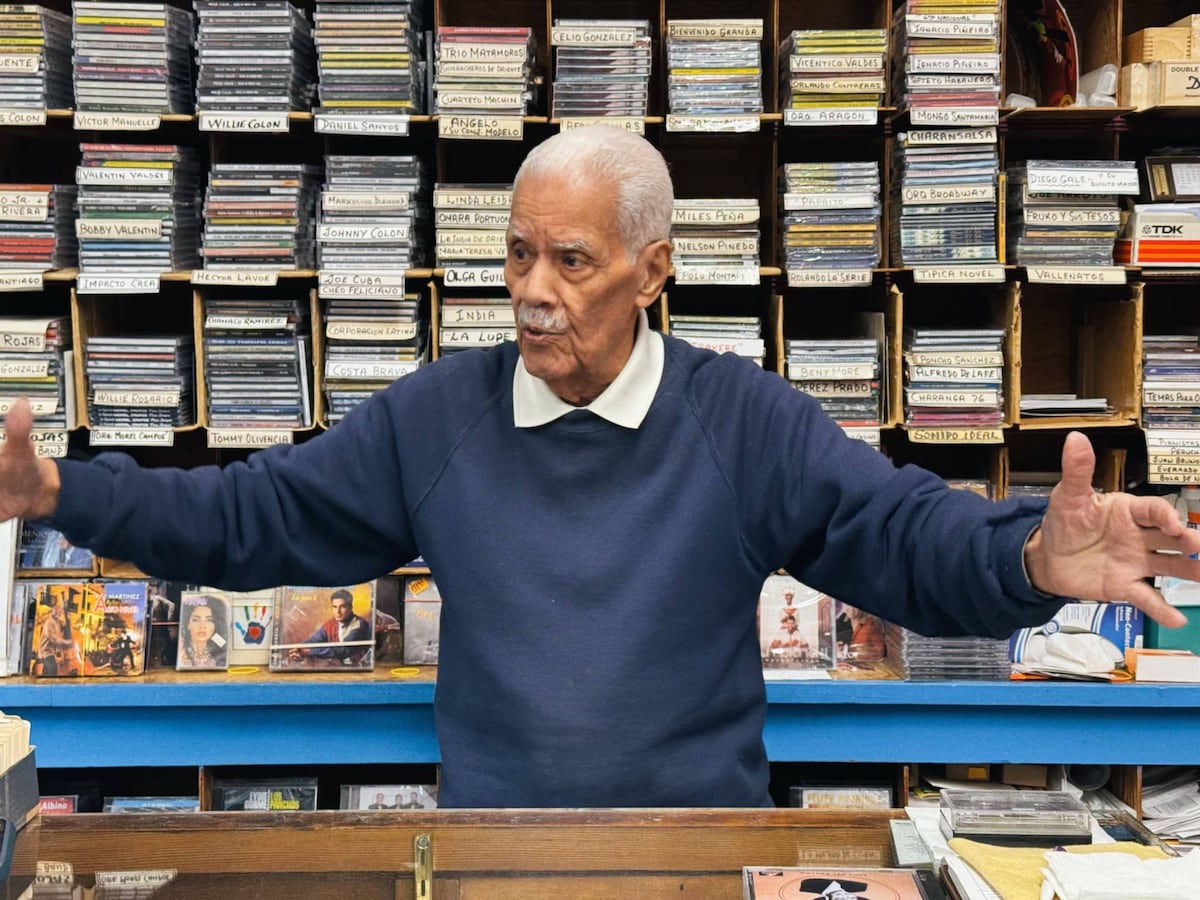

Amadeo is more than a record seller. He composed some of the most emblematic songs of Latin American music such as Que me lo den en vida, sung by El Gran Combo de Puerto Rico, or Oye mi consejo, sung by Celia Cruz. He also collaborated with other giants of the genre such as Héctor Lavoe, altogether composing more than 300 songs.

In 1955, Amadeo’s life changed forever. After working as a musician in bars and restaurants, he was offered a job at the Alegre Records label, which specialized in Latin American music. He didn’t think twice. Playing one album after another on one of those radio cassettes that are already museum pieces, Amadeo says that he does not identify with what the general public recognizes as the genre of salsa. “To talk about genres such as plena and bomba is just an invention,” he says.

Music runs through his veins because he is the son of the composer and musician Titi Amadeo, although he “soon abandoned us,” he says, referring to himself, his mother and his brother. His nephew is Tito Nieves, one of the most successful contemporary salsa singers. Casa Amadeo opened its doors in 1941 as Casa Hernandez — the second store of Puerto Rican music entrepreneur Victoria Hernández and her brother, popular musician Rafael Hernández. In 1969, Amadeo acquired it and gave it the name it maintains to this day.

There is no one on the premises to help him. “For what?” he asks. “How many customers have you seen come in here?” Although the clientele is no longer what it used to be — you can count them on the fingers of one hand — there is not a single day when Amadeo leaves the shutters down. He is open from Monday to Saturday and is always ready to sing, talk and, of course, sell a record, which go for around $15 a piece. He rarely has recent releases, and his customers don’t always know what they’re looking for, but they’re sure to find something interesting. It’s cash only; no cards. Amadeo has the entire inventory in his head, and points to a box where there are handwritten cards in alphabetical order, like an old telephone directory.

After all these years in New York, Amadeo still feels like an islander — as Puerto Ricans are known in New York — and doesn’t want to be labeled a New Yorker. “I am Puerto Rican,” he says. And when asked if he likes reggaeton, or his compatriot Bad Bunny, he replies: “I hate reggaeton. It’s nothing personal, but I believe in the form.”

Although he does not say it directly, Amadeo knows that he is irreplaceable. What happens to the store when he is no longer around does not matter to him either.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

[ad_2]

Source link

Comentarios